Traps in the Alps – A Reflective Essay on Gell’s Traps and Linying’s Alpine

This essay was written as coursework for NUS SC2225: The Social Life of Art.

Using Gell’s discussion of enchantment and traps, choose one art object (a painting, a photograph, a song, a book) that enchants and captivates you. Why are you attached to this particular art object? How does it surprise and seduce you?

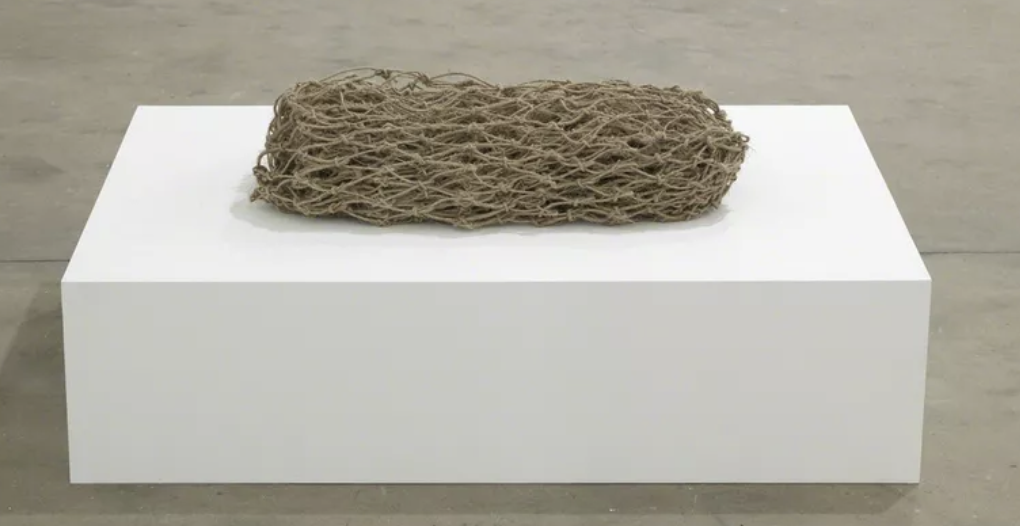

It is difficult to see the Zande hunting net as more than a found object or a curatorial choice. However, to understand the crux of Gell’s traps, one has to further deconstruct the ‘trap’ into an intentionally chosen a thing that ensnares. The sociocultural implications of the trap are then revealed through how and what it ensnares, in turn opening up layers of interpretability for said trap. This is the lens through which I will be unpacking my chosen art object – a song, ‘Alpine’, written and performed by Linying – a trap I have been enchanted and captured by.

‘Alpine’ begins with faint, gradually amplified drone. It is coupled with carefully dropped synthesised notes that reverberate within its quiet soundscape. Prompting me to increase the volume, the song is gentle with its ascension, drawing me in with its clear arc that climaxes at its chorus. This is how ‘Alpine’ enchants: storytelling through sound that exhibits the technical virtuosity of its production.

Vogel’s Net, 2013. Replica of a Zande hunting net, rolled and bound for transport as displayed in the exhibition Art/Artifact at the Center of African Art, New York 1988.

Source: www.artsy.net/artwork/mariana-castillo-deball-vogels-net

As Gell states, my “[recognition of] the technical procedures used (173)” engenders my appreciation for it. While not a sound producer myself, I recognise the implementation of a narrative arc in the musical phrasing, and the intentionality in the track’s timbre and dynamics to evoke a sense of forlorn hope (which is also reasserted lyrically). Hence, I can appreciate the artistic intention and the effectiveness of execution. Similar to how found objects evolve into artworks when the artist mindfully chooses and composes them, to me, this is where the composition of found sounds actually evolves into music, becoming art.

The genius of ‘Alpine’ also lies in its awareness of its audience and its position within music (i.e. “the domain of social relations (178)”). Amassing about 3.7 million streams on Spotify (extremely high for a Singaporean artist) and featured on Spotify compilations like “Haunting Vocals” and “i’m not crying you are.”, Linying is undoubtedly conscious of her niche and fits snugly into it. Considered an electronic-pop artist, the atmospheric voicings of ‘Alpine’ is also characteristic of this genre. Hence, it references other emotions listeners associate with music from this genre (isolation, longing, sadness), reiterating the themes of the song. Furthermore, this ability indicates an “acquisition of technical facility (176)”, where Linying has effectively internalised the style of such music and repurposed it into her song.

As with most music, the listener is first entranced by ‘Alpine’s’ overall sound before noticing its lyrical brilliance. When reading the lyrics while simultaneously listening to the song, another layer is unveiled. This is where Linying’s storytelling becomes more detailed, conjuring specific images through her visual language. From enveloping the listener in high altitudinal alpine breezes, grounding them in grocery store aisles, to isolating them within vast space, imagery transports the listener, enhancing the listening experience. Romantic images of “cherry hills” are contrasted against the stark reality of loneliness in bed in the morning, reflecting the artist’s navigation between reality and idealism. Hence, a feeling of longing amid lost is evoked. The lyrics add a layer of bittersweetness to the foundational sadness previously conveyed by the sound. Furthermore, as a Singaporean listener, I am compelled to draw on my personal experiences and attempt to situate Linying. In a country with neither cherry hills nor alpine breezes, her image choices appear more ethereal, accentuating the notion of romanticism.

Additionally, Linying manages to employ a consistent rhythm and rhyme despite barely having word repetition (which even when used, is an artistic choice that cues listeners to compare verses). Thus, sound and lyrics work congruent with each other. The prudent song writing ensures that its lyricism does not overwhelm the song’s flow. Abstraction is also done in moderation such that it is still accessible as a pop song. Hence, Linying skilfully threads the intersection of music and poetry, melding writing with music to create a multifaceted sensory experience that captures the listener. As a poet myself, this casts Gell’s Halo-effect of technical difficulty. In understanding Linying’s work, I subconsciously place myself relative to her, where my comparison allows me to acknowledge her virtuoso as both a writer and musician. This heightens the enchantment effect, hence drawing and holding me in the art-trap.

The effectiveness of Linying’s communication of these ideas within ‘Alpine’ also contributes to its enchantment (albeit a self-reinforcing effect). To implicitly communicate such a nuanced emotion of forlorn hope towards a lost relationship in music is a feat that carries an extent of uncertainty. Similar to the uncertainty Gell expresses in gardening, this is an uncertainty created by the variables influencing the outcome of the technical process. In this case, it is successful audience reception. ‘Alpine’ manages to tug at just the right lyrical and sonic strings, culminating in an intense depiction of the intended emotion. It identifies common reference points and taps into the shared emotional experience of a multitude of listeners –– all without ever explicitly stating said experience. This unexplainable feat hence contributes to ‘Alpine’s’ enchantment, and I see it as nothing short of magical.

‘Alpine’, in its technical excellence, enchants its audience. Its ability to appeal musically, lyrically, and visually (through imagery) help “activate the human’s capacity to respond aesthetically” (187). Hence, based on criteria of Aesthetic Theory, it is art. While it lacks historical or cultural context (being about an emotion), its symbolic song writing also gives it interpretability, hence abiding by Interpretive Theory as well. Therefore, ‘Alpine’ converts from an artefact (i.e., a mere composition of sounds) into art.

On the other hand, ‘Alpine’ also allows an understanding of art as traps. From the viewpoint of the audience (victim) and the artist (trapper), there is an anticipation of the audience’s response (as how specialised Pygmie traps anticipate chimpanzee responses) (198). Linying incorporates imagery, word choice, and sound, using their connotations and society’s emotional associations to them to effectively convey emotion. The art thus becomes a vessel, containing atmospheres of isolation, forlornness and longing. As a trap, ‘Alpine’ surprises with its aesthetic choices, and seduces with its technical excellence and effectiveness. Just like an alpine breeze, it brushes past you in an unexpected chill that stops you in your step, captures your attention, and leaves you wanting more.

Works Cited

Gell, A. (1999). The Art of Anthropology. New York: The Athlone Press.

Source: www.pbs.org/wnet/nature/files/2021/01/pexels-denis-linine-714258.png

Listen to Alpine by Linying here: